By Dr. Craig D. Reid

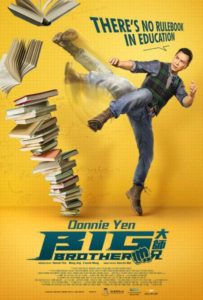

Donnie Yen’s latest film, Big Brother, is a Hong Kong drama that deals with social and racial issues in an inner city school. Sound familiar? It’s a film influenced by To Sir, with Love (1967), which was directed by James Clavell, who is mostly known in Asia for his literary Asian Saga novels that includes Shogun and two historically based Hong Kong stories, Tai Pan and Nobel House.

Directed by Kam Kai-ka (assistant director on Yen’s Ip Man and Ip Man 2), Yen plays former US Marine Henry Chen who returns to Hong Kong to be a teacher at his former school on a mission to find himself, which deepens as he helps five wayward kids find themselves, find their parents and with a little typical Yen rough, tumble and bash, save the school from going under due to land grabbers, under achieving students and gangster ne’er do wells.

Ultimately it’s Yen and Chen battling the inadequacies of Hong Kong’s education system and how the five troublesome secondary school students are dealing with alcoholism, gang violence, sexism, racism, poverty, suicides, bullying, class discrimination and cigarettes. Roll call caricatures: tomboy girl with a younger brother; twins, one with ADD the other into video games, dealing with a alcoholic father; a pissed off kid living with and supporting his grandma who can’t find housing; and a Hong Kong-Pakistani kid treated like crap by students and Chinese police while dreaming of becoming a Canto-pop star.

Yen has things to address and he does so not by complaining or ranting on about it, which is really common these day, but with a character that finds solutions and applies them with happy calm smiles, a good ear, plenty of high fives and fist pumps and assuring you can do it and believe in yourselves adages. The final challenge to the kids and the audience is to contemplate over the age-old question, “What is the meaning of life?”

Yen has high hopes for Big Brother saying that as a father he’s faced many issues during his own and his children’s education. “I understand the stress students have these days. I also try to be a good teacher to my kids. It’s why I made this film…bring awareness to today’s students’ issues, while bringing positive energy, motivation for kids and entertainment at the same.”

He points out that society’s atmosphere can shape us, yet during the worst of situations, try to see things positively and you may find hope. Conversely, even if you live within a prosperous economy, if you adopt negative attitudes toward facing problems, you’ll still find something to be unhappy about. Though the film is about education, the ultimate goal is to remind viewers that life is beautiful.

What set’s apart Big Brother from all the other inspirational school dramas that have dotted America’s landscape with teachers trying to make a difference with inner city students is Yen’s unique ability to intersperse his patented elaborate, high energy fight scenes that are not there because they have to be (although for any Yen fan they’re needed), they’re there to fulfill the film purpose and add to the objective at hand.

What set’s apart Big Brother from all the other inspirational school dramas that have dotted America’s landscape with teachers trying to make a difference with inner city students is Yen’s unique ability to intersperse his patented elaborate, high energy fight scenes that are not there because they have to be (although for any Yen fan they’re needed), they’re there to fulfill the film purpose and add to the objective at hand.

Yen posits, “Let’s face it, people want to watch the action, so if the action can lure fans, students and parents into cinema, good. We don’t lecture anyone, we provide entertainment. Stephen Chow is a great example of this: you laugh through his movies, but they’re not just silly comedies; they have meaningful messages to convey. That’s what I’m hoping to achieve here.”

If I was a Hollywood fight choreographer, stunt coordinator or film director who’s been making martial arts movies over the past four years, with all the big budgets, star power, actors training for their roles, special effects with everything available to do what is perceived to be ground breaking action…after watching this film, I’d be depressed as hell.

If I was a Hollywood fight choreographer, stunt coordinator or film director who’s been making martial arts movies over the past four years, with all the big budgets, star power, actors training for their roles, special effects with everything available to do what is perceived to be ground breaking action…after watching this film, I’d be depressed as hell.

The three fights Yen puts together, which we’re all waiting to see what he pulls off in regard to how the fights remains within the movie’s subject area, reflects how far American fight scenes have not come along. Yen’s fight are like guitar solos by Jimmy page, Eric Clapton and Jimmy Hendrix, while Hollywood fights are still stuck on the foundations of the great guitarists Chuck Berry, T-bone Walker and Les Paul, which isn’t a bad thing, it just represents that the fights haven’t truly evolved into what they should be…and there’s no excuse for that anymore.

The film’s English title infers that Yen is maybe the kind of older brother the kids never had. The Chinese title Da Shi Xiong is a term used in kung fu schools to indicate that he is an elder to other kung fu students who has been in the school longer than those who call him da shi xiong. So in a wacky way, it has a kung film sensibility.

For the fight scenes, Yen hands over the fight choreography duties to his long-time collaborator Kenji Tanagaki who has been with Yen since Yen’s first directed film Legend of the Wolf (1997), where Yen introduces high speed ways to batter bodies, wreak havoc on heads, and flatten faces with high octane desperate angst vitality and bashing ferocity.

Yen has often hinted that if he was younger, he could’ve been a champion MMA fighter, which no one to date has argued his point of confidence. It was in SPL (2005) when Yen showed his prowess doing MMA inspired fights that even back then, his first attempt, to this day still dwarves anything Hollywood MMA fight scenes have offered. This is not a knock on UFC champions that have appeared in American made MMA inspired films, they just lack the cinematic look and rapid fire skills that give the action the wild and wooly excitement seen in his movies. In fairness, it’s comparable to any Western boxing fight scene seen in Chinese films, they don’t measure up to what we see in Hollywood films that feature boxing.

Big Brother not only features Yen’s entertaining martial histrionics but it may be his best MMA influenced fights he’s done as he mixes his flashy spinning body rolls and wrap around grappling skills that lead into real and newly created MMA holds and locks. The first fight features Yen thrashing a group of white MMA fighters preparing for a bout night during an over-top-top locker room brawl that highlights a duel against the film’s future MMA Champion, Night Fare (French MMA fighter Jess the joker Liaudin; 84+ MMA fights), where Yen’s imaginative use of old-style metal lockers as unique weapons is way beyond the call of madness and mayhem.

In regard to his experience with school violence, Yen closes, “By being a minority in American schools, I’ve encountered bullies every day. Luckily, I started learning kung fu at the time and Bruce Lee was very popular. I dressed like Bruce Lee at school every day. The kids knew I am good at martial arts, so they didn’t do anything to me.”