With a beautifully constructed allegory mirroring William Ernest Henley’s 1875 poem Invictus that asserts, “I am the master of my fate: I am the captain of my soul,” the record breaking Chinese 3-D animated feature Ne Zha, which is loosely based on a Chinese mythological martial arts legend drawn from the Ming Dynasty novel The Investiture of the Gods (aka The Creation of the Gods) written by either Xu Zhong-lin (unknown-1566) or Lu Xi-xing (1520-1601), rivals the riveting glitz, glaze and glare of anything DreamWorks or Disney has swirled out over the past 20 years. Earning $650 million in 30 days, Ne Zha features eloquently stylized martial arts action, camera choreography perfection and pays meticulous attention to flawless martial postures, skills and weaponry that come with the godly bravado and spiritual sustenance that only Chinese filmmakers can understand and do.

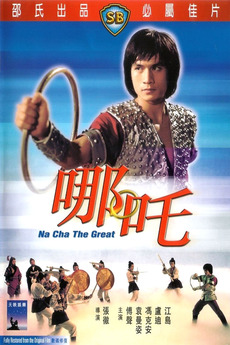

Since Mao Zedong took over China in 1949, Jet Li’s Shaolin Temple (1982) is considered to be the first Communist Chinese martial arts (MA) film. Yet to be technical about it, the animated feature Nezha Conquers the Dragon King (1979; NCDK) is the first People’s Republic of China film that features MA. The various stories of the Chinese deity Nezha (Ne Zha, Na Zha, Na Cha) and the antics with his kung fu ring, spear and fire-wheel feet have been featured in several earlier live action and animated Chinese films. The most notable being the Chang Cheh directed Shaw Brothers films Na Cha the Great (1974), where NCDK is a more fantastic retelling of Chang’s version. However, NCDK is the first film to reveal Nezha’s legendary birth and his eventual three-face reincarnation on one head. How appropriate is it that 40 years since NCDK, China’s biggest animation feature of all time is also based on Nezha.

According to Chinese folklore, in many cases, one has to do some amazing things in their life to become a Chinese god. When such people die and ascend to heaven, they have to, for lack of a better way of describing it, apply for godhood. When an application is rejected, usually because the applicant feels he is more important and benevolent than he really is, things can go awry. Without professing to be any sort of expert on Chinese gods, of which there is about 154 at last count, this subtle subplot may have not been grasped by Western audiences in Ne Zha.

Directed and written by Yang Yu (aka Jiao Zi, which means dumpling), Ne Zha opens with the fly whisk wielding Taoist monk Taiyi and his kung fu brother Gongbao brandishing a briar looking sectioned solid sword, dueling the fiery crystalline Chaotic Pearl who because of absorbing the essence of the sun and moon to become a conjoined Immortal and demon, it has blurred the line between good and evil.

Successfully distracting it, the Supreme God Yuan Shi Tian Zun steps in, splits the Chaotic Pearl into the blue Spirit Pearl and the red demon pill, and traps them inside a purple lotus blossom. Because the demon pill is dangerous and indestructible, Yuan casts a heaven-made curse so that a lightening bolt will kill it in three years. Yuan snubs Gongbao and tells Taiyi that he is guaranteed a place in Heaven as the last Golden Immortal if he can make sure that the Spirit Pearl reincarnates into the third son of Lord Li and Lady Yin, protectors of the inhabitants in Chen Tang Pass. When that happens the son will be called, Nezha.

Fate goes awry as the scorned Gongbao steals the Spirit Pearl and delivers it to the Dragon King, the plan being that the Spirit Pearl who by becoming the King’s son Oa Bing, will become unstoppable and the give the dragons a chance to escape their purgatory existence and the King will have a chance to become a God. If this all works out, Gongbao believes he and not Taiyi, will become the final Golden Immortal.

Meanwhile, the demon pill becomes Li and Yin’s son Nezha. The only way to suppress Nezha’s evil nature, creating havoc and slaughtering everyone is for Taiyi to place the Qiankun Hoop (golden ring) around Nezha’s neck like a necklace. One fear is that if Nezha figures out how to release the gold ring, the world will be screwed. Yet the parents want to keep Nezha as their son and hope that by helping him become more balanced, a good person, then the heaven curse might be reversed. The father swears that regardless of the outcome, he will die by Nezha’s side trying to help him to the end.

As martial folklore dictates, Nezha is a protection deity of Taoist mythology who is often depicted as an impish young trickster holding a flame-throwing spear in one hand and that golden hoop (aka cosmic ring) around his right shoulder. Nezha zips around the sky via a flaming wheel under each foot. Interestingly, the Chinese invented a flamethrower lance in 200 B.C., which was a spear connected to a tube filled with gunpowder that spewed fire from the tip. This spear was the forerunner of the first cannon.

Born 3,000 years ago, Nezha is the third son of military commander Li Jin. When born, Nezha was a ball of flesh. After his angry father struck the ball with his sword, Nezha flew out, and although he instantly grew to adulthood, he had the mind and attitude of a child. Nezha is famous for killing two demonic deities: rain god Third Prince Ao Bing and the yaksha (nature god) Li Gen. Ao Bing’s father Ao Guang, who was Dragon King of the East Sea, kidnapped Nezha’s parents and demanded Nezha to disembowel himself in order to save them. However, Nezha was brought back to life and given great powers by the Taoist immortal Taiyi. He used lotus blossoms given to him by the immortal Ran Dang to rebuild and reincarnate Nezha into a warrior with great powers; this angered Nezha’s father, causing them to fight each other. Nezha was superior to his father, so Ran Dang learned to control Nezha by unleashing a purple cloud from his sleeve that could trap him inside a burning golden pagoda. Eventually, the Jade Emperor stepped in and united father and son into becoming heroic demon slayers.

The movie Na Cha the Great (1974) launched the cheeky, lovable persona that Alexander Fu Sheng became famous for, a caricature that truly separated him from the whole stable of Shaw regulars and irregulars. Enhanced by the fight choreography of Liu Chia-liang and Tang Chia’s kung fu weapon choreography, the plot closely follows the legend except that Nezha killed the gods Li Gen and Ao Bing for trying to beat up a young man who was trying to stop Li and Ao from trying to rape the young man’s fiancée. The other exception is that according to the legend Nezha and his father did not make peace and ended up at each other’s throats for eternity.

Of note in NCDK, when Taiyi arrives on the back of a white crane and feeds Nezha a speck of pollen, Nezha grows into full boyhood and is given a red scarf and a gold ring. What follows is Nezha performing two intricate ribbon-and-ring rhythmic gymnastic routines to Olympic-style music, which are two of the main tools used in rhythmic gymnastics. This could be a nod by the filmmakers to point out that the athletic art has its roots in ancient China wherein martial arts and acrobatic street performers used rings and ribbons for dramatic effect. When Nezha becomes a young adult and fights the Dragon King and his minions, his fighting routines and spear twirling forms, which are accompanied by Beijing opera music, take on a more pure martial arts flair.

In Jiao Zi’s Ne Zha origin story, he takes full advantage of today’s cinematic technology as reflected by 1318 special effect shots, where the Dragon King’s mysterious underwater dungeonic Dragon Palace and the astonishing finale battle between Ao and Nezha used 1600+ animators from 20 special effects studios working around the clock for three years. Ironically the age of Nezha when he is supposed to meet his demise?

His updated version is full of slight of hand, mouth and nose humor, gleeful grossness, Chinese tongue-in-cheek whimsy (some are lost in the English translations), visual gags that show Jiao Zi’s fandom of certain Hollywood-made films, and refreshing new takes on the source material in regard to the fights against the sea demon bubble spewing yaksha and giving the impish Nezha a contemporary shtick such as the whack-a-mole shot, the comical “disguising spell” scenario, handling kid bullying with booby trap tom foolery, the cute as cute can be surprising backup pig, the importance of friendship and an amazing painting spectacle scene reminiscent of a 1967 TV episode of Robert Conrad’s The Wild Wild West.

The Fights of Ne Zha

The fights are ultra-kinetic and use beautiful special effects shots with variable speed action within a single martial skill and quick cuts, all of which is almost standard in Hollywood live-action films. The difference here though is that in animation, it enhances the action and offers grandiose comedic interludes between each shot without detracting away from the emotion and smoothness of the fights, where in American made live-action movies these are all done to hide the ineptitude of the actor fighting, the directors inability to know how to shoot a fight and a choreographers lack of creativity to make a non-MA actor look authentic. There are of course some exceptions, where in my opinion…the fights in John Wick 3 are the best because the movie focuses on camera choreography and did long takes using wide angle camera work so you can see who’s doing the fights and the length of the shot emotionally draws you into the fight.

Another advantage of animation, which Ne Zha takes full advantage of is the use of camera choreography during the fights. Virtual cameras can move in, out, around, within, without and where ever by a flick of a switch, so to speak. Yet what makes the MA action so beautiful is that in Ne Zha, attention to detail of the martial arts in regard to posture, stances and technique are as close to perfect as any human.

In MA films, you can tell which actor really know MA when the hand or the arm of the fighter not being used to block or punch remains in a correct position during technique application. Nailing a perfect stance in MA is as important a nailing a gymnastic pose after the end of one’s demonstration. Animated characters have no excuse to do poor MA unless of course that is part of who the character is. Since this film’s main characters are perfect kung fu practitioners, some even training for hundreds of years, they’d better look good dynamic…and they do.

Apart from Ne Zha’s flaming spear, another important weapon of note highlighted in the film is Ao’s bulbous ice hammers (melon-shaped weight on the end of short poles), a cudgel that was widely used during the Spring and Autumn, and Warring States periods. Due to it’s melon shape it was often times referred to as the standing or lying melon. Eons ago, men who used these weapons were call Golden Melon Warriors.

A second neat aspect of the film is the missing link in the evolution of whips. At the film’s beginning, Gongbao wields a briar looking solid multi-sectioned sword, yet at the end of the film there’s a piece of martial weapon ancient history that’s not explained. The most well-known whip weapon to kung fu practitioners is the soft whip, aka the nine-section whip (jiu jian bien), which is comprised of nine slender pieces of steel connected together to form a whip-like weapon. At the distal end of the whip is a steel knife point. The weapon was originally a solid iron weapon with nine vertebra-like sections fused together like a pagoda or a piece of bamboo, as is Gongbao’s sword, which was called a hard whip. Although the history is not clear, it seems that the transition stage, or missing link if you will, between the hard and soft whips was a bullwhip-looking weapon consisting of nine long, thin, tightly connected metal sections. Thus the sudden use of his weapon changing….not magic…merely part of martial history.

It’s things like this and the fights of Ne Zha that sets it apart from Japanese anime and anything from a Pixar, DreamWorks or Disney production that feature MA fighting characters…they don’t understand the complete histories, and don’t know how to make the fighters and action pure of skill with the grace of a crane, the power of a tiger, the nimbleness of a monkey, the speed of a mantis, the smooth rhythmic endurance of a snake and how the dragon rides the wind. There are feelings and emotions that you can’t see, yet they’re in Ne Zha.

Similar to Marvel films, be sure to watch the end-credit scenes, four of them to be precise, where the filmmaker comically remind you to watch them.