In Zhang Yimou’s latest wu xia drama set during China’s Three Kingdom Period (AD 220-280), Shadow (mandarin Ying, translation Shadow), Zhang’s palace intrigue twisted tale of lies, deceit, power plays, doppelgangers and a wonky love triangle, features two purposely chosen kung fu weapons, da dao (a long handled big sword blade) and umbrellas that makes Singin’ in the Rain more dangerous than tap dancing in a mine field.

The most famous kind of da dao in Chinese history is the guan dao, a highly venerated, giant-bladed halberd created by the Kung Fu God, Guan Gong (aka Guan Yu), a hero during the Three Kingdoms, his face depicted in folklore by a red face and long black beard. In a bit of irony missed, based on which Mandarin romanized rules are applied, sha dow means kill with a sword.

The Pei Kingdom is rule by a fractious caitiff (Zheng Kai) who’s more interested in keeping peace at the cost of his power and seemingly has a crass disregard toward honor as he whines about how he’s fine with the enemy Yan Kingdom occupying Jing City in the heart of Pei territory for the past 20 years. This occurred when Pei’s army Commander Yu (Deng Chao) was defeated by the Yan’s powerful Commander Yang (Hu Jun) during a mano a mano battle inflicting Yu with a damaging, lingering wound. Jing City was the prize for the victor. As Shadow begins, and without the permission of the Pei king, Commander Yu tells the king that in seven days there will be a rematch to similarly decide the future of Jing City. In panic, the Pei king plans to duck war and maintain peace by volunteering his beloved sister to be a concubine to Yang’ son.

Seems clear enough until…Yu isn’t really Yu, but a mirror image of himself, a no name poor commoner who because he has an uncanny resemblance to Yu, was plucked as a child from the home of his blind mother, renamed Jing (déjà vu, Deng Chao). Jing has become a slave peasant shadow and is being primed and trained by the real Yu, who lives in the palace’s secret chambers, to exact revenge against Yang and agitate the king’s cowardly pacifism. Yu’s wife (Sun Li) joins the collusion avowing that shadow Yu is the real Yu and the Pei king is none the wiser. Yet Yu and Yu are passionately in love with the same woman, who becomes torn between two husbands.

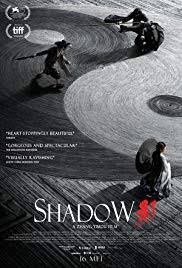

After Zhang’s soulless, made for Hollywood The Great Wall (2016) floundered like a possum playing dead for too long and was thus buried for real, Shadow is a prodigious rebirth of his of powerfully poignant imagery eloquently wrapped in a 50 shades of gray motif. Zhang shares that apart from only highlighting character skin tones and emphasizing lipstick red, blood letting, the influence behind his absorbingly monochromatic glazed luster stems from using the ancient Chinese art of traditional ink brush painting that only uses differing concentrations of black where the brushwork emphasizes the perceived spirit and essence of the subject over direct imitation.

Zhang explains, “This style of brushwork art expresses my understanding of this complicated thing called humanity. Humanity is not black and white, it’s like an ink brush painting, yet with is, it’s something in between. That is the unique character, patience and complexity of a human being. We created sets that were as complete as a painting.

“It’s easy into today’s special effects world to shoot in color and make the film look like it was shot in black and white. We didn’t use CGI. We used specific colored materials in our set designs and building complex structures and also used real objects to achieve the desaturated effect. Everything on the set, every prop, costume, silk used in the screens and weapons had to be black, white or a combination of the two.”

Even the locations look liked they were shot during May gray rainy days and under June gloom cloudy skies. Its visual palate also embraces the principle of yin meets yang to reflect the theme of duality, where a small white circle is in the black half and a small black circle is in the white half, so as in life and opposites, it’s not all black and white. When Bruce Lee added a white arrow outside the black half and a black arrow outside the white half, pointing clockwise, it represented that in martial arts the energy also flows around in circles and between the black and white.

The Fights of Shadow

I first met Zhang in 2004, when my wife was his translator for the LA-based press junkets for House of Flying Daggers. Back then he shared with me that he sold his blood twice in one day to buy his first camera. After working night shifts for seven years in a fabric-making factory he accidentally got into filmmaking. When he entered film school, his friends called him crazy, thinking that film school was about learning how to run a film projector. Yet through all the anemia of life, the struggles of the Cultural Revolution, and chastising of his friends, Zhang emerged as one of the top influential martial arts movie filmmakers in the third millennium. Not bad for a guy that didn’t know about Bruce Lee until 1979 and by 2004 had only seen 15 martial arts movies.

“It’s not that I don’t like the films,” Zhang explained in Mandarin. “Growing up during the Cultural Revolution, we never saw these films, they weren’t available. It wasn’t until film school that I learned about Bruce Lee. When I saw my first Bruce Lee film, I thought, ‘Oh my goodness.’ At that time I also saw my first wu xia films. It was wonderful.”

Back then his favorites were Tsui Hark’s Dragon Inn and King Hu’s Touch of Zen adding, “I also liked Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon. But actually my films are really a nod to King Hu and of course my wu xia films are also in homage to all the great wu xia films I’ve heard about over the years, but sadly haven’t had time to watch.”

Note for hard-core wu xia fans. In the engagingly enthralling 116-minute Shadow, a movie fit for art houses and the drooling International Film Festivals that have been long awaiting Zhang’s Shadow to arrive, it features 12 minutes of martial action. Yet consider that the darling of these same film festivals three years prior were similarly salivating for the highly anticipated Assassin (2015), the debut kung fu film from Taiwan’s Hou Hsiao-hsien, featured much less martial action. Yet the pacing of Shadow’s fights are more similar to the highly popular 1970s Shaw Brothers director Chu Yuan, who often highlighted many short fights strategically interspersed throughout his films.

Historically, the Three Kingdoms period focuses mostly the Wei, Shu and Wu kingdoms between the years of AD 220-280. In regard to the Yan and Pei kingdoms highlighted in Shadow, the State of Yan arose during the Zhou dynasty (1046-256 BC) and was defeated by the Pei Kingdom in AD 222, then Pei was eventually absorbed into the Wei Kingdom. Of note, as previously mentioned, Guan Gong was one of the greatest general is Chinese history who fought for the Shu kingdom and used a da dao weapon called guan dao, the only da dao weapon that had an exceedingly wide blade and a back spur. As a nod to Guan, director had Yang’s da dao have a back spur.

It’s not until minute 56 where we see any combative action of consequence, as Yu prepares to take on Yang. It’s during the lead up to the duel when the principles of yin yang are beautifully addressed as a means to counter Yang’s deadly expertise by revealing the balance that exists between the female and male components of combat.

It’s customary in Chinese martial folklore that each martial arts style and often times great fighters, have a signature skill. Yang’s indomatable technique never fails to kill an opponent within three movements (translated in English as round 1, 2 and 3).

In Shadow, Yang’s secret is recognized when he sprints away from his opponent with the blade dangling behind him scraping along the rain swept ground then as Yang spins around to block his opponent’s attack, his body falls backward to the ground as he swings his blade down and strikes the opponent’s neck. It takes less than 10 seconds to shoot.

Therefore, each time we see the skill, it’s shot in slow motion, so the audience clearly sees how the skill is applied during combat and importantly in Zhang’s view, to bring out the poetry of the movement. Yang’s weapon weighs 40 kilos and in a neat twist for wuxia films out of China that predominantly wield feather weight weapons used by wushu tournament competitors, actor Hu Jun convincingly makes the weapon look and feel heavy.

For those interested, in the 1982 Legendary Weapon of China, the final 16-minutes feature actors Liu Chia-liang and brother Liu Chia-rong using 18 different real weighted weapons, including a real guan doa. It’s wild to witness.

One glaring error for non-martial artists to be aware of in Shadow is that film says in Chinese and also translates into English that the yin yang symbol is called the tai chi symbol. The principle of yin yang arose in the third century BC, the movie takes place circa between AD 220-280 and the martial art taiji (aka tai chi) was created in AD 1365.

The da dao is a manly man heavy bladed weapon requiring great masculine strength and power, so the simplicity of an umbrella could be overlooked as a potential weapon, yet when deployed with an exquisite feminine touch it can be quite foxily efficient. Thus it was about a male warrior to get in touch with his feminine side, similar to how in the early days of Chinese opera, female characters were oft played by men, their first lesson always about learning how to walk like a women. Now Jing and the Pei fighters have a signatory skill, except the weapon isn’t made of material but slashing steel femblades.

“The use of the umbrellas was my personal creation,” Zhang shares. “But they’re based on the yin and yang concept in Chinese esthetics. When you have a strong, tough power you must counteract it with soft power, so yin energy overcomes yang energy. The umbrella becomes very shiny and slippery in the rain, so the concept is: discharging the force of the enemy.”

Imagine how wacky it would be if you and your army were armed with razor sharp, bludgeoning blades that can cut a man in half and your suddenly facing a small army of men that just Trojan horsed in, swam underwater in a swampy river that doubles as a sewer and now they’re traipsing around in the rain soaked streets of Jing City holding umbrellas and walking toward you as if they’re on their way to have tea and cakes at an English garden party. The masterstroke to Zhang’s ink brush painting sensibility is the dazzling fight choreography of Ku Dee Dee and how the nuances of the yin yang combative subtexts are preserved throughout the film amid the chronic rainfall and the acute blade ballets. The sheer audacity to even think about doing this outrageous palate of combat and to get away with it, this alone, makes the film worthy of watching.

On a final comment Zhang shares, “It took a month to shoot all of these rain-soaked action sequences thus we needed to use rainmaking machines that used different sized spouts that could make big drops, small drops and drizzling drop. We shot under this watery conditions constantly, so the actors were always drenched.”